Socrates in Pre-Trial Detention Learns about Zeus

And then gets totally abandoned by his new teacher. It's enough to make a man want to choke back some hemlock.

In other incarnations of the digitalverse, divers discussions were spawned when some quarterwit decided to toss out the old faff about atheists not having any basis for morality, despite Immanuel Kant existing.

As always in discussions of divine command morality, I summon all the smugness my bachelor’s in philosophy can provide1 and remind people that Plato definitively solved this problem 400 years before the common era in one of his dialogues, entitled “Euthyphro.”

For those not familiar with how ol’ Broadsides2 related philosophical matters to us mere mortals, Plato had characters in dialogues discuss the ideas, usually his tutor Socrates with various other people. Each Platonic Dialogue is named after the principal interlocutor (e.g., Timaeus, Meno) or otherwise the subject of the scene (e.g., The Apology, the Symposium). We do NOT have original written accounts by Plato, if indeed he did write them down, but largely second- or third-hand copies of notes made by his students.

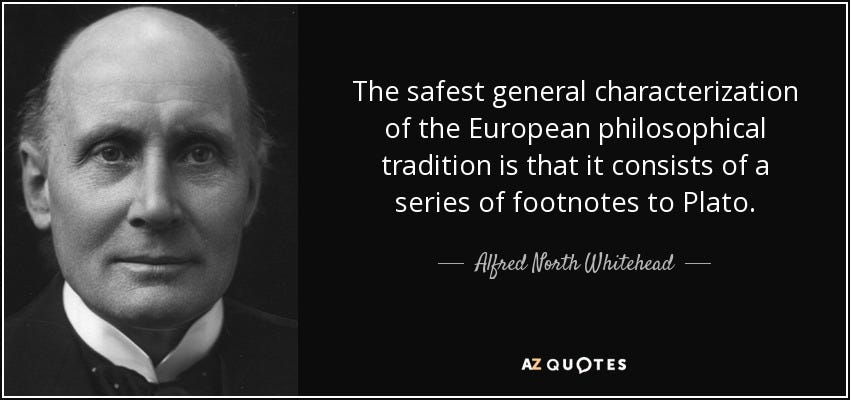

Nevertheless, and I say this without shame and hyperbole, there was never a greater philosopher born that Plato. His student Aristotle comes close. The greatest masters of the modern period, like Descartes, Hume, and Kant, come close. Other giants of the field, like Frege, Hegel, Heidegger, or more recently the late Saul Kripke, can maybe find a dim candle to hold next to Plato. But when Alfred North Whitehead quipped that all of western philosophy was a series of footnotes to Plato, he was not overly exaggerating.

Almost every topic we discuss in modern academic philosophy finds its genesis in Plato and his contemporaries, who were the first, as much as we can tell, to synthesize philosophical reasoning apart from mythopoeic or religious metaphysical and ethical thought and start attempting to systematize it into a rational discipline.

The Euthyphro represents Plato’s attempt to reason through the problem of good and evil and God’s place in it in a systemic fashion. It is, I believe, one of the singular most important pieces of writing in the philosophies of religion and ethics in the Western canon. Everyone should read it, because it is not terribly long, not hard to understand, but has left us pondering its questions 2500 years later no closer to having arrived at a solution than Plato himself, flexing his muscles on his opponents and talking in dialogue in the marketplaces of Athens.

The dialogue begins with Socrates at court, awaiting his trial for blasphemy and corrupting the youth of Athens. A rival philosopher of the Sophist school, Meletus, has gone to the Athenian authorities and brought a lawsuit against Socrates, claiming that the latter’s method of philosophical inquiry and doubt as to the cocksure conclusions of the Sophists has led the youth astray into impiety.

Euthyphro, another learned man of the city, is also in court to prosecute his own lawsuit, and happens across Socrates. Euthyphro asks Socrates what gives, and Socrates says, “lol Meletus sucks.”

So Euthyphro rejoins, “well… you do say occasionally that some unknown tutelary divinity speaks to you, giving you wisdom beyond other men3.” And Socrates replies with, “Oh, that, but ordinarily people don’t care as long as you’re not trying to convince someone else to do what you want them to do.”

Euthyphro responds with, “yeah, and everyone likes me, because, unlike you, I’m not constantly going around baiting people into dialogues where I try to change their minds.”

And Socrates is like, “chill, dog, I just love the people so much I feel like I’ve got to tell people. And it’s not for money; I would pay people to listen to me, so badly do I feel the need to hear myself talk.”

As the two begin to banter, it becomes apparent Euthyphro is there to sue his own dad for the crime of murder, as Euthyphro’s employee at his farm apparently got drunk and slit another worker’s throat. Euthyphro’s dad decided to have this worker tied up and thrown in a ditch, which was apparently what you did at the time. Unable to decide the matter any further, Euthyphro the Elder sent for a priest to adjudicate the ethical ramifications of binding and ditch-throwing, but in the time it took the priest to saunter over, the the worker in the ditch died of exposure.

Now, surely at this point ol’ Soccy was thinking, “this is the great ethical quandary you have? C’mon, Euthy, the answer is easy: bind the man, let him wait for trial, but don’t let him fucking starve while you wait for the judge.” Nevertheless, because Socrates never missed an opportunity to be an asshole, he engages with Euthyphro about the whys and wherefores.

Socrates says: “well hold on, big dog, even if everything is as you describe, aren’t you committing a greater impiety by suing your dad, since admittedly you don’t know anything more about what the religious laws are than him?”

Ruffled, Euthyphro responds that because he is the great Euthyphro, noted litigator of Athens, he of course has knowledge of these matters in greater amounts than other men. Otherwise people would not seek him out to plead their cases.

So Socrates responds, “Oh wonderful! Then since you are so wise, brother Euthyphro, allow me to become your devoted student, so that I might in some way take some of your reflected glory in my own dispute with that villain Meletus! Surely he wouldn’t dare say a student of the great Euthyphro was a blasphemer!”

Now Socrates has him by the balls pride, and Euthyphro is hooked in the dialogue. So Socrates pops the first question on him.

So now, by Zeus, explain to me what you were just now affirming to know clearly: what sort of thing do you say holiness is, and unholiness, with respect to both murder and everything else? Or isn’t the pious the same as itself in every action, and the impious in turn is the complete opposite of the pious but the same as itself, and everything that in fact turns out to be impious has a single form with respect to its impiousness?

Euthyphro explains that piousness is like what he is doing now, prosecuting the wrongdoers. Impiousness would be failing to prosecute wrongdoing. And if great Zeus did not want us prosecuting even our parents, why then did Zeus lead the Titanomachia and bind his own father Cronos for the crime of devouring his children?

Socrates then asks Euthyphro, “nah, bro, for real? You seriously believe the Titanomachia was exactly as the poets relate?”

And Euthyphro, ever pious, says of course I believe in the Titanomachia. I am a very godly man.

And Socrates continues, “no doubt, no doubt. But I did not ask you to teach me some pious things; I wanted to know about piety itself.”

Euthyphro thinks about it, and responds that:

Well, what is beloved by the gods is pious, and what is not beloved by them is impious.

This is the statement we have come to call “divine command” morality. That is, good things are good because God calls them good, and evil things are evil because God says so.

Now, class, do we think ol’ Socrates was satisfied with this answer?

So Socrates at first locks him down: “Euthyphro, is it your testimony that actions or things loved by the gods are good, and actions or things unloved by the gods are bad?”

When Euthyphro agrees, Socrates busts out with this:

But wasn’t it also said that the gods are odds with each other and disagree with one another and that there are feuds among them?"

Euthyphro admits this is ever so. Socrates asks him, “let’s say we’re counting the apples on that tree. And I say there are 50, and you say there are 55. Would we swear a blood feud and agree to disagree, or are we going to go over there and count some apples?”

Euthyphro admits they’ll just count the damn apples. Socrates points out a few other things: in matters empirical, where the test of truth is measurement, that’s what he and Euthyphro would do to determine it.

But since we know Euthyphro is a pious man and believes the Homeric tales of Zeus and the Olympians as told by the poets and mystics and religious naffs, we know that the Olympians do not simply resolve their disputes over what is to be beloved and what is to be hated by such means. Rather, the Olympians fight and scheme and fight and fight and fight over what they love. Socrates points out that this would make the same things both pious and impious depending on which god you were asking.

So Euthyphro says, “yeah, but c’mon, we’re not talking about whether Athena or Aphrodite or Hera is hotter4 we are talking about killing a man! Surely no god out there thinks killing someone without just cause is good!”

So Socrates merely points out that “without just cause” is the subject of a billion Athenian lawsuits. And Euthyphro responds with, “yeah, but I have the power of reason. And if you would but listen to my reasons, you would be compelled to reach the same conclusion because I am such a great reasoner.”

So Socrates, in his brilliance responds, “yeah, but I’m kinda fucking dumb. You might be able to make it clear to the learned judges the particulars of a situation, but you’ve gotta do more convincing because I’m not as smart as you.”

They go on, and Socrates allows Euthyphro a brief respite: he will allow him to reform his divine command theory thus —

The pious is that which is beloved of all the gods, and the impious is that which all the gods detest.

Now Socrates has him, and asks him this humdinger of a question:

Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved?”

For those of you who, like Socrates, are a bit slow, let me, the great Euthyphro the Younger, explain with my peerless reason: Socrates has just phrased a central metaphysical question about the nature of goodness. Is what we think good good merely because God commands it so? If so, then God himself is not “good.” God is merely the arbiter of “goodness,” but that places God beyond good and evil. He is no more subject to the moral law of the universe than a tyrant is subject to his own laws.

But most (modern, Christian) theologians would dispute that this conception of God applies. After all, it is central to Christianity that God is not only worthy of worship due to his power and status as ruler of the universe, but that God is a good of infinite goodness and the epitome of all perfections. If God is equally as evil as he is good because moral considerations do not apply to him, then that poses a problem for Christianity.

But it also posed a problem for Euthyphro 500 years before anyone heard of Christianity. Because Euthyphro was now in a similar pickle: Zeus and the Olympians loved things that were good, he said, and so he seems be implying that goodness is a quality the gods can recognize apart from their mere whims.

But if the beloved and the pious were in fact the same, my dear Euthyphro, then, if the pious were loved because of being the pious, then the beloved would be loved because of being the beloved, and again, if the beloved was beloved because of being loved by the gods, the pious would also be pious by being loved. But as it is, you see that the two are opposites and completely different from one another, since the one is lovable because it is loved, and the other is loved because it is lovable.

Socrates has trapped Euthyphro in a reductio ad absurdum. The reasoning is now circular.

Euthyphro gets grumpy at this point and accuses Socrates of trying to lure him off topic. Socrates reminds him that the definitions of divine command morality they have been using come solely from Euthyphro himself.

The debate continues with Socrates granting Euthyphro the correctness of his definitions, but asks instead whether piety and justice are the same. Euthyphro responds that piety is a part of justice, specifically the part concerning attending to the gods. That is, we say “piety” is justice toward the gods, while justice toward other humans is justice apart from piety.

Euthyphro goes on to explain that what he means is that a person who studies piety and justice learns that there are correct ways to behave, which provide for the common good and human flourishing. Socrates asks:

So piousness for gods and humans, Euthyphro, would be some skill of trading with one another?

Euthyphro is here again forced to confront the absurdity of his statement: he is back to saying that good things are beloved by the gods because they are good, and the gods love good things because they are what the gods love. That circular reasoning about whether “goodness” is an independent property of the gods has returned.

Now, why is this important to our modern moral discussions? Because, as pointed out by innumerable philosophers, but most famously Kant, if good is independent of God’s whim, then good can be discovered by the application of reason. Like Socrates’ gods, we can discover what is good, and choose to love the good, independent of the whim of the divine.

Oh, how does the dialogue end? I was afraid you’d ask that. Socrates points out that Euthyphro has reasoned himself in a circle again, and Euthyphro suddenly remembers he has business elsewhere. Socrates responds:

What a thing to do, my friend! By leaving, you have cast me down from a great hope I had, that I would learn from you what is pious and what is not, and would free myself from Meletus’s charge, by showing him that, thanks to Euthyphro, I had already become wise in religious matters and that I would no longer speak carelessly and innovate about these things due to ignorance, and in particular that I would live better for the rest of my life.

As the kids say, the shade of it all.

However, in his backhanded way, Socrates has shown us something: “goodness,” as a property, exists apart from simple divine command. If God is the merely the arbiter of what is good and bad, and decrees on high, then he is a tyrant, akin to Conan’s Crom. There is some historical evidence that these conceptions of God as good were not universal; for instance, in the Hebrew Bible, and pre-rabbinical Judaism, one could make the argument that Yahweh is not himself “all good,” but merely the all-powerful ethnic God of the Hebrews who deserves worship for that reason. And certainly, in the 300-ish years following Plato, Jewish and early Christian (not to mention neoPlatonic) thought would wrestle with the idea of a demiurgos, or creator god who was himself corruptible or evil, as opposed to the notion of a transcendent God of pure wisdom and light who was the embodiment of all things good.

Nevertheless, the Euthyphro represents a divergence in the history of philosophy and a definitive refutation of divine command theories of morality. If your position is that “good” and “bad” are merely the things your god calls good and bad, then the problem is that if I do not recognize the authority of your god, your reasoning means nothing to me. And that position would be a minority position among the world’s major religions, almost all of which believe that their deity is itself fundamentally good.

And so if “goodness” is a property independent of God, to which even God must be subject to judgment of a criterion as “goodness,” then morality, like God, would be transcendent of any particular human experience or instantiation. Like Socrates, we are not asking for examples of good things; we want to know about goodness itself. And if goodness may be discovered, and loved for what it is, then the application of reason can lead us to determine what is good, the same as it can lead God to determine what is good as well.

Thus, atheists, as much as theists, can determine what things are good by asking after the form of goodness, and need not be bound solely by the directives of the voices of the divine.

Which is “considerable,” verging on “vast.”

Plato is a nickname. His real name was Aristocles, but acquired the nickname “Platos,” meaning “broad” or “big” because he was a wrestler.

In Greek mythology, a “daimon” was a spirit that occupied a middle place between gods and humans. Socrates stated that he occasionally heard the voice of his “daimonion” (sign of the daimon) warning him against certain actions. But this was not a voice that imparted specific, propositional wisdom. The daimon would not tell Socrates “hey bud, do this,” so much as when Socrates did not feel the sign of the daimon upon him, he tacitly assumed his personal tutelary spirit was fine with whatever he was going to do.

Cause of the Trojan War, look it up, dummy.